-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Shaji Sebastian, Huw Jenkins, Sarah McCartney, Tariq Ahmad, Ian Arnott, Nick Croft, Richard Russell, James O. Lindsay, The requirements and barriers to successful transition of adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: Differing perceptions from a survey of adult and paediatric gastroenterologists, Journal of Crohn's and Colitis, Volume 6, Issue 8, September 2012, Pages 830–844, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crohns.2012.01.010

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Background and aim: Preliminary data highlight the importance of appropriate transition for successful transfer of adolescents with IBD from paediatric to adult care. The aim of this study was to identify both the perceived needs of adolescent IBD patients and the barriers to successful transition from the perspective of professionals involved in their care.

Methods: A postal questionnaire was distributed to UK adult and paediatric gastroenterologists with an interest in IBD. The questionnaire utilised closed questions as well as ranked items on the importance of the various competencies of adolescents with IBD required for successful transition.

Results: Response rate of 62% and 49% for paediatric and adult gastroenterologists respectively was achieved. A structured transition service was perceived as very important by 80% paediatric compared to 47% adult gastroenterologists (p = 0.001). A higher proportion of adult than paediatric gastroenterologists identified inadequacies in the preparation of adolescents for transfer (79% and 42%, p = 0.001). The main areas of perceived deficiency in preparation identified were patient lack of knowledge about the condition and treatment, lack of self advocacy and co-ordination of care. Lack of resources, clinical time, and a critical mass of patients were the factors ranked highest by both groups as barriers to transition care. Both adult (65%) and paediatric gastroenterologists (62%) highlighted suboptimal training in adolescent medicine for adult gastroenterologists.

Conclusions: This survey highlights differences in the perception of adult and paediatric gastroenterologists in the management of transition care and perceived competencies for adolescents with IBD. Lack of training and inadequate resources are the main barriers identified for development of a successful transition service.

1 Introduction

Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis first present in childhood and adolescence in approximately 25% of patients and the incidence in children appears to be increasing.1 This growing cohort of patients will require transfer from a family focussed multidisciplinary care model in paediatrics to an adult system where patients are expected to be independent and make their own decisions on the management of their inflammatory bowel disease.2,3 In addition, data suggest that patients diagnosed with colitis and Crohn's disease at a younger age often have a more aggressive disease which makes the timing and process of this movement even more important.3,4

The orderly process termed transition is applicable to all chronic diseases including IBD and is defined as ‘the purposeful, planned movement of adolescents and young adults with chronic physical and medical condition from child-centred to adult-centred healthcare system’.5 There is increasing consensus, albeit largely based on expert opinion, that a co-ordinated transition is vital in patients with chronic gastrointestinal problems including IBD.6–8 Research in other chronic diseases such as diabetes and congenital heart disease has reported that successful transition is associated with improved disease outcome.9,10 However, the ideal transition service is not yet defined in IBD and the establishment of such a service may be dependent on local organisational and patient related factors.11 Several barriers to effective transition programme have been elucidated in other chronic disease settings5,12,13 but there is limited data about these in IBD transition. A previous survey14 has looked at the experiences of adult gastroenterologists in IBD and identified that co-ordination and communication between health care teams were lacking. However this survey was limited by low response rates and lack of involvement of paediatric gastroenterologists.

This study aimed to identify the perceived transition requirements of patients with IBD from the perspective of adult and paediatric gastroenterologists involved in their care. The information obtained will be useful in formulation of care models and guidelines for effective transition programmes in IBD.

2 Methods

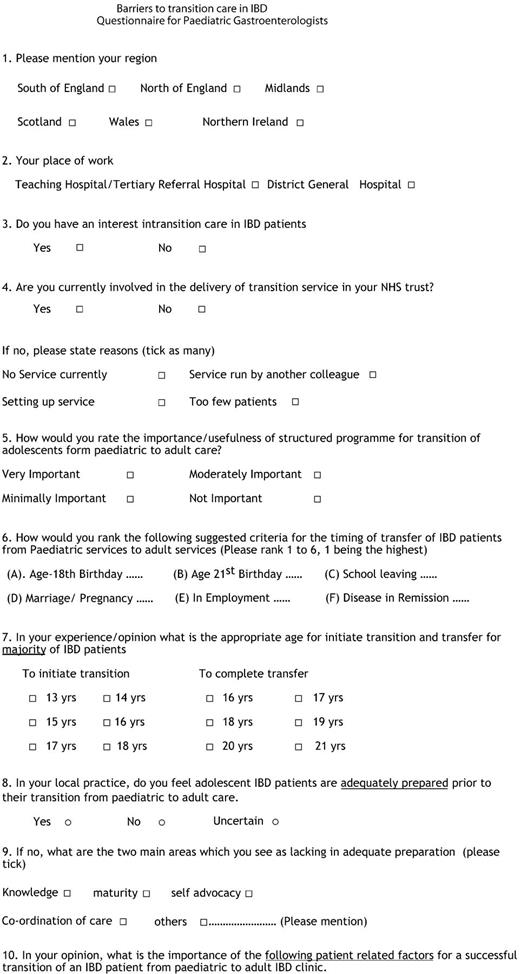

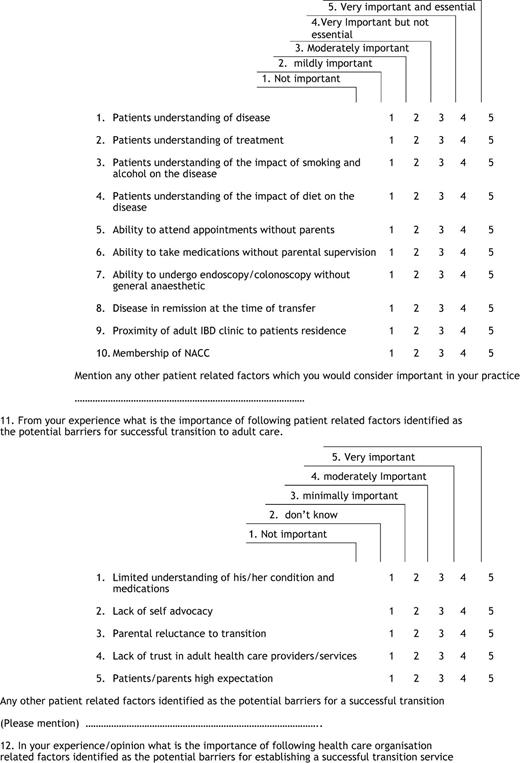

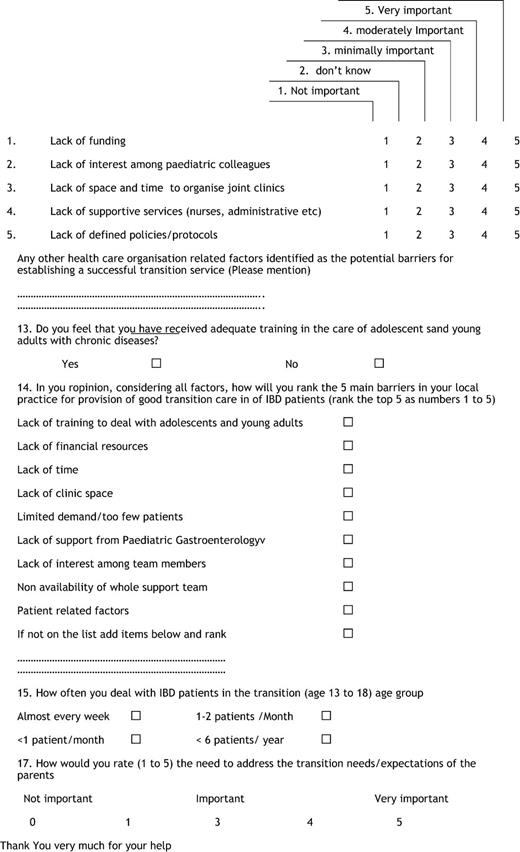

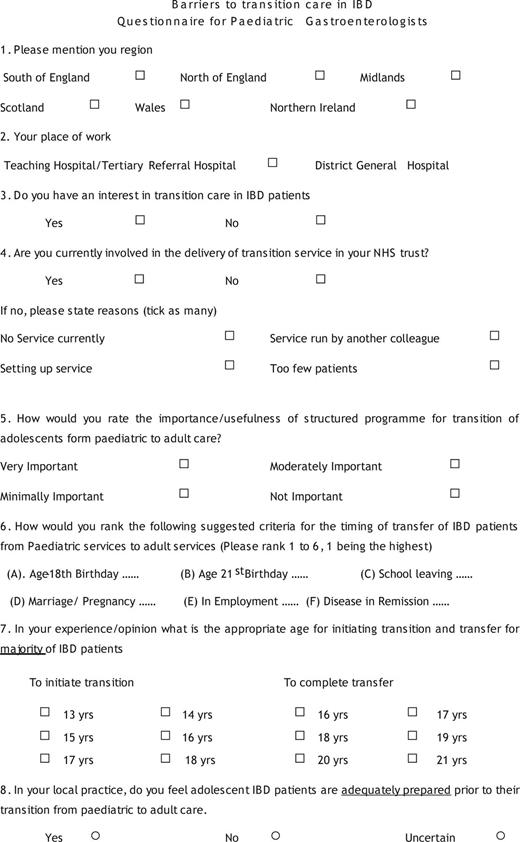

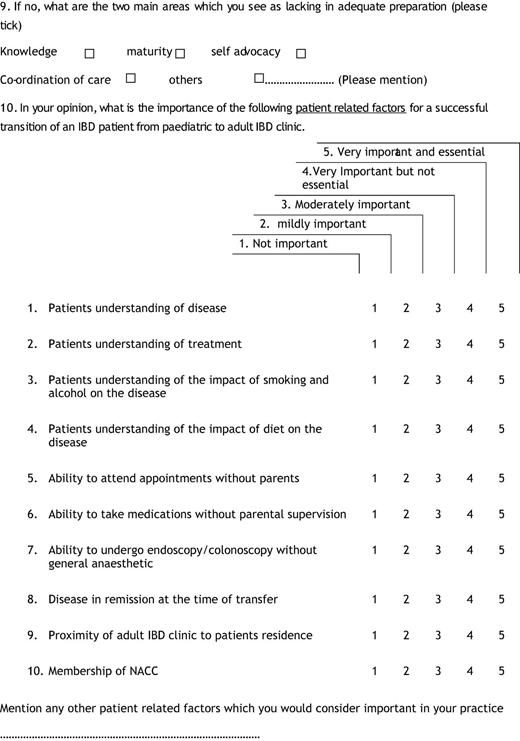

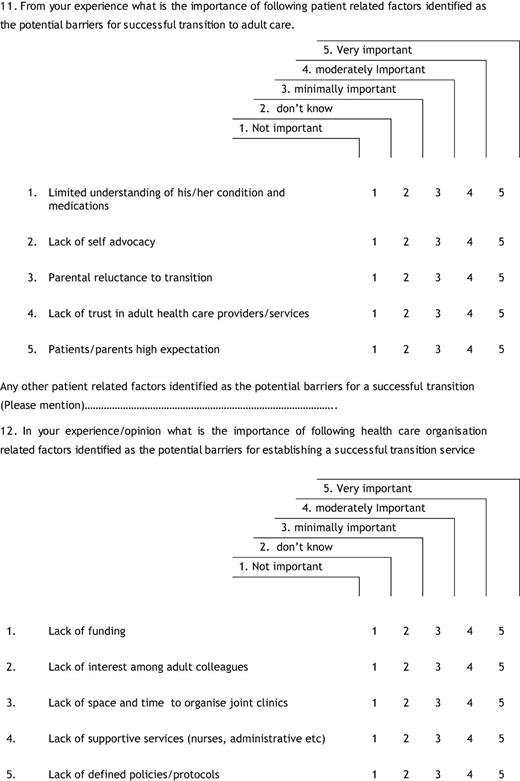

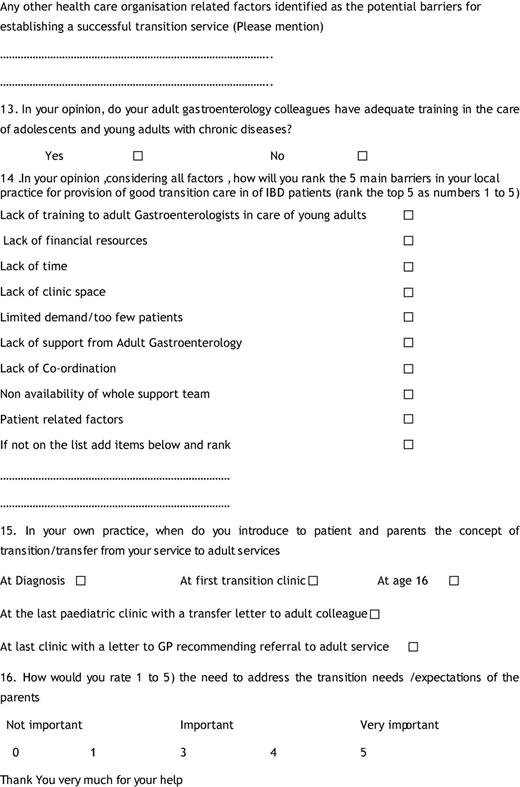

A structured postal questionnaire designed for self completion was developed by the Adolescent and Young Persons Section of the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) comprising both adult and paediatric gastroenterologists. The 16 item survey contained forced choice and open ended questions concerning three main areas including current status of provision of transition care in United Kingdom, perceived needs for effective transition care in IBD, and the organisational, clinician and patient related barriers to successful transition. The participants were also asked their opinion on the relative importance of medical and developmental issues in IBD patients during transition and transfer. The responses were ranked on Likert Scale of 1 to 5 anchored by ‘1 = not important and 5 = very important and essential’. There were minor differences in the surveys sent to adult and paediatric gastroenterologists in 2 of the relevant questions (sample survey is enclosed in Appendix 1).

Adult gastroenterologists involved in care of IBD patients were identified from the membership of the IBD section of the British Society of Gastroenterology. Paediatric gastroenterologists and general paediatricians with particular interest in gastroenterology were identified from the British Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition membership. Participants were excluded when correct contact information could not be obtained. Because this study was structured to obtain data from practising gastroenterologists involved in the care of IBD patients we also excluded hepatologists, exclusive academic gastroenterologists and retired clinicians.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Version 16.1 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Demographics such as geographical and institutional settings were described as proportions as were the responses to closed questions. The other items were ordered according to mean ± SD of Likert-Scale rating and then compared using Students T test. Wilcoxon signed-rank test and Spearman correlation were used for number of responses in order to ascertain which factors predicated a significant perception in adequacy of transition or barriers. The threshold for statistical significance was set at p = 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 Demographic of responses

The survey was sent to 729 adult gastroenterologists and 132 paediatric gastroenterologists. A higher response rate was achieved from paediatric gastroenterologists (62%, 82/132) as opposed to adult gastroenterologists (49%, 358/729) (p = 0.01). In the adult group, a further 17 returns were deemed invalid due to 8 respondents not being in active practice or recently retired 9 being returned unfilled/with limited completion and hence not included in analysis. The geographical location and the hospital setting of the respondents are given in Table 1.

Among responding adult gastroenterologists a significant proportion (211, 59%) was not currently involved in delivery of transition service. The reasons cited for non-involvement included the absence of such a service (85, 40%), too few patients (38, 18%) or because the service was run by a colleague (73, 34%) while 6% was in the process of setting up the service. Forty eight (58%) of the paediatric gastroenterologists who responded were involved in the transition care in their institution, the remainder were not involved due to lack of service (11, 32%), service run by another colleague (15, 44%), setting up service (6, 17%) and too few patients (2, 6%). A larger proportion of responding paediatric gastroenterologists (74, 90%) expressed interest in transition care when compared to adult gastroenterologists (236, 66%) (p = 0.05). To the question on the number of patients in the transition age group of 13 to 18 years which they deal with in their practice (311 of the 358 responding adult gastroenterologists answered this question), 34 (11%) saw such patients almost every week, 73 (24%) saw 1–2 patients per month, 66 (21%) saw average 1 patient per month and 136 (44%) less than 6 patients per year and 2 reported never seeing such patients.

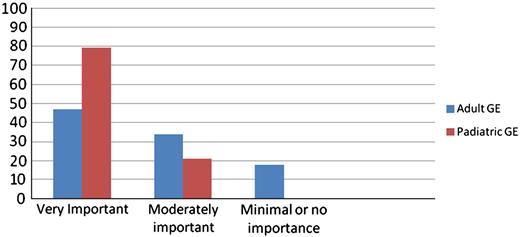

3.2 Perceived importance of structured transition

The respondents rated the importance of a structured transition as laid out in the UK national framework for children as very important, moderately important, minimally important or not important (Fig. 1). There was a significant difference in the perception of the importance of structured transition service with 47% (162/358) of the adult gastroenterologists and 79% of the paediatric gastroenterologists describing the value of a structured and individualised transition as very important (p = 0.001). Moderate importance was attributed to transition care by 34% and 21% of adult and paediatric gastroenterologists respectively. While 18% of adult gastroenterology respondents felt that the need for transition care is minimally and/or not important none of the paediatric gastroenterologist expressed this view. Participants from the teaching hospitals described transition of high or moderate importance compared to their counterparts working in general hospitals (p = 0.01). There were no significant differences in this response based on geographic regions.

3.3 Timing of transfer

Both groups identified age as the most common criterion for initiation of the transition process and completion of transfer with the suggested age being 16 (45, 56% of paediatric and 254, 70% of adult gastroenterologists) and 18 years (68, 82% of paediatric and 289, 81% of adult gastroenterologists) respectively. However a significant proportion (22%) of paediatric gastroenterologists suggested an earlier age of transition at age 14 and some (2%) felt that the transition process should start at diagnosis of IBD irrespective of the age. There was no statistically significant difference observed in this response from different regions or based on the status of the hospital.

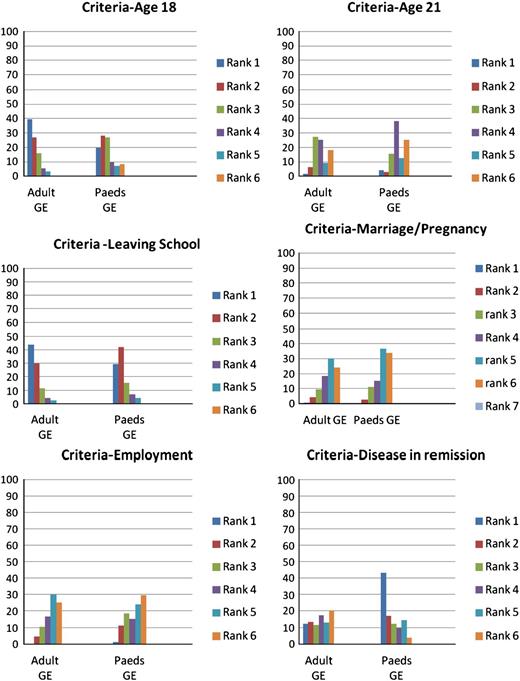

The highest ranked milestone for completion of transfer was leaving school (42% and 29% of adult and paediatric gastroenterology respondents respectively) and this overall matched with their ranking estimation of the age of transfer at 18 (37% and 23% respectively). A significantly higher proportion of paediatric gastroenterologists (43%) ranked a status of disease in remission as the most important factor for timing of transfer as compared to adult gastroenterologists (12%, p = 0.0001). The percentages of respondents giving rankings 1 to 6 for various criteria/milestones for transfer are given in Fig. 2.

3.4 Adequacy of preparation at transfer

A higher proportion of adult than paediatric gastroenterologists identified inadequacies in the preparation of patients for transfer (79% and 42% respectively, p = 0.001). When asked to identify the two main areas as they see as lacking in adequate preparation, the adult gastroenterologists identified suboptimal patient knowledge about their condition and its treatment (35%) and co-ordination of care (40%) while paediatric gastroenterologists identified problems in self advocacy (30%) and co-ordination of care (34%): there were no statistically significant differences in the perception of adequacy of preparation based on geographic region or institutional status. Involvement in transition services by the respondent appears to reduce the perception of inadequate preparation (r = − 0.28, p < 0.05).

3.5 Perceived importance of patient competencies

The patient related factors and competencies for successful transition receiving high mean scores of perceived importance from the respondents included patients' understanding of the disease and its treatment and their ability to take medicines independently. The paediatric and adult gastroenterologists attributed similar importance to majority of patient related competencies (Table 2), but differed in their mean scores in the need for the patients to attend clinics without parents which was considered more important by the paediatric gastroenterologists. In contrast, the adult gastroenterologists rated the ability to undergo endoscopies without anaesthetic higher in comparison to paediatric gastroenterologists.

3.6 Perceived barriers to transition

Among organisational factors which are perceived as potential barriers, the lack of space and time, lack of funding and lack of supportive services were the main issues identified. The main patient related barriers identified were the lack of self advocacy and the limited understanding of the condition and its treatment. The responses from paediatric gastroenterologists suggested that lack of interest by adult services and lack of trust in the adult clinical services with significantly higher mean scores of importance attributed to these factors in their responses when compared to the corresponding responses from adult gastroenterologists. The mean scores of health care organisation and patient/parent related factors which are perceived as barriers to successful transition are presented in Table 3. There was correlation between lack of interest in adult colleagues as a barrier and District General Hospital status (r = 0.45, p < 0.005). In addition, lack of support services and space as barriers to transition correlated positively with District General Hospital status and northern region (r = 0.6, p < 0.001 and r = 0.34, p < 0.05 respectively).

When asked to rank the top 5 obstacles individual respondents were experiencing in their local setting in delivering a transition service, the responses were similar for both adult and paediatric gastroenterologists (Box 1).

Lack of funding

Lack of time

Lack of support services

Too few patients

Lack of training

3.7 Perceived training issues

When asked about their perception of the adequacy of training in adolescent care of their adult gastroenterology colleagues, a significant proportion of paediatric gastroenterologists (59%) responded as suboptimal training. Similarly 224 (65%) of the adult gastroenterology respondents acknowledged that they have received inadequate training in this area. The perception of inadequate training was less from teaching hospital respondents (r = − 0.27, p = < 0.05). The challenging aspects identified by adult gastroenterologists in managing individual IBD patients in the transition age group included patients' psychosocial needs, patients' lack of independence and high parental expectation. When asked about the importance of addressing the transition needs of the parents, the mean rating scores (1 to 5, 5 being utmost importance) given by paediatric and adult gastroenterologists were 3.42 +/− 0.98 and 3.78 +/− 1.1 respectively (p = NS).

4 Discussion

The relapsing and remitting nature of IBD and its impact on the physical, developmental and psychological states of adolescent patients make successful transition a priority.15 Establishing clear guidelines in transition care in IBD has proved difficult due to a lack of randomised controlled trials involving this group of patients, variations in care in different clinical facilities and differing approaches to management.16,17 An appreciation of the current service provision and barriers to its delivery from the perspectives of key stakeholders is crucial to aid the design of pathways of effective transition using available resources.18

This survey provides a comprehensive assessment of the current perspectives of two key stake holders in the process of transition in IBD—paediatric and adult gastroenterologists. A recent survey among clinicians involved in IBD by Hait et al.14 surveyed only adult gastroenterologists and had a low response rate of 34% thereby raising the possibility of response bias. Our survey included both adult and paediatric clinicians involved in care of IBD patients and had better response rates of 49% and 62% respectively. A previous study from UK showed wide variations in provision of care,19 therefore we included a wide geographical area involving all the home nations in the British Isles and a variety of clinical settings.

Our survey of clinicians shows that the timing of transition should be flexible. The suggested age for initiation of transition was similar between adult and paediatric respondents, although the paediatric clinicians preferred to introduce the concept of transition early to their patients. In contrast, for transfer a social milestone such as leaving school around the age of 18 was the favoured option by both groups of respondents. This age for suggested transfer was similar to surveys in other chronic diseases.18 In a survey of adult and paediatric programme directors in cystic fibrosis centres, age of 18 was the main criterion for transfer.20 For many patients the age 18 coincides with the end of secondary schooling and transition to university education or employment and these changes in social context could also be a trigger for changes in medical care.21 Parents and patients in studies on transition in IBD cited age of around 18 as an appropriate timing of transfer.22,23 It was interesting to note that, as in the case of the cystic fibrosis survey,20 other ‘adult’ events such as marriage and pregnancy were not considered to be major criteria for transfer in our survey. Paediatric clinicians seem to attribute the state of remission of the disease as an important aspect when considering the timing of transfer. Disease in remission was a key marker for timing in the original transition recommendations.6,24

Ideally transfer should happen only after the young patient with IBD has attained the necessary skills to function in an adult clinic setting. In our survey 79% of adult gastroenterologists felt that the patients transferred to their clinics had suboptimal preparation prior to transfer. The key areas identified by the adult gastroenterologists were suboptimal knowledge about their condition and its treatment and coordination of care while the main issues raised by paediatric gastroenterologists were coordination of care and lack of self advocacy. It was interesting to note that involvement in the transition process reduced the perception of inadequate preparation in both adult and paediatric gastroenterologists. Similar results were also reported in the survey by Hait et al.14 where 55% and 69% of respondents reported deficits in knowledge of condition and medication regimes in the young adults transferred. Without proper transition with all the documentation, there may be tendency for the new adult service to embark on a complete reassessment at the first meeting which can be very unsettling for the patient. There are tools available now to assess the readiness to transfer in IBD25,26 and other chronic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis.27 The best known of these is the My Health26 passport for IBD designed for cross sectional assessment of the knowledge of the patients and parents which facilitated education and independence in the transitioning adolescent with IBD. While not designed to assess their usefulness, the results of our survey suggest that such tools if validated may have a useful role in the transition process.

In our survey, there appears to be some differences in the perception among adult and paediatric gastroenterologists about the relative importance of various patient related factors which are important for successful transition. The paediatric gastroenterologists in our survey rated the status of the disease in remission and ability to attend clinics independently as important aspect for successful transition. In contrast the ability to attend clinics independently by the young patient was a concern only for 15% of the respondents in the survey by Hait et al.14 Knowledge of the disease and its treatment and the understanding of the impact of life style issues such as smoking were considered important by both groups. The adult gastroenterologists in our study felt that the young person should have the ability to undergo endoscopy without use of the general anaesthetic a finding also reported in the study by Hait et al.

The recent UK national IBD audit reported that only 27% of the sites had established transition service and many of them were simple handover clinics28 although a small survey recently shows some signs of improvement.29 Similarly less than 60% of the paediatric gastroenterology centres in France had an organised transition care arrangement.22 This status of transition care may be due to several potential barriers to transition, as suggested in the medical position statement of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatoloy, and Nutrition6 and our survey bring forward many of these barriers. In our survey both adult and paediatric respondents identified a lack of time, space, funding and support services such as IBD nurses were ranked as the key obstacles which they face in clinical practice. While there is data on other chronic diseases,30,31 to our knowledge ours is the first study in the field of gastroenterology to identify these practical issues. In contrast to a study by Peter et al.,32 our respondents did not report high parental expectations and lack of interest in specialists as barriers in transition care. Limited demand was one of the reasons identified by a proportion of respondents in our study. However, as indicated in a survey of rheumatology services in UK providing transition care for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, another chronic disease like IBD, small size clinics may be considered as strength in view of the complex transition needs of this patient population.33

Our survey raised important issues in relation to training in adolescent medicine particularly for the adult gastroenterologists. Similar to our study, training in adolescent care was identified as an issue in the study by Hait et al.14 as well as for transition in other chronic rheumatological and cardiac diseases.34,35 The respondents in our survey from teaching hospitals and those with established transition services seems to have a perception of adequate training which may imply joint and collaborative working practices. A collaborative approach to transition between paediatric and adult gastroenterologists may offer education in its own right; for examples adult gastroenterologists may transfer their experience in managing pouchitis as indicated in a survey from UK of surgical practice.36At the moment adolescent medicine is not incorporated in specialist training of adult gastroenterologists in many countries including the United Kingdom and our survey indicate the need for developing such programme in IBD.

The format of the transition services available in our survey varied from simple handover clinics to a more structured adolescent service involving both adult and paediatric gastroenterologists. More paediatric gastroenterologists reported involvement in the transition service in their institution and rated a structured transition service as ‘very important’ when compared to their adult colleagues. In a retrospective case control study of IBD patients in a dedicated adolescent and young adult clinic, Goodhand et al.37 showed that specialist transition clinics have benefits including reduction in exposure to diagnostic radiation. Similarly a small French study of IBD patients and families undergoing transition reported their visit to the joint clinic as a positive experience.22 Furthermore, good correlation between the number of joint clinic visits and readiness to transfer was found in an established transition programme for IBD patients in Netherlands.25 However, the number of appropriate patients and resource issues as identified in our survey may hamper development of such specialist clinics in all but the larger centres. Clearly randomised trial data on the benefits of a transition programme are needed and hence there is a great deal of interest on the results of an ongoing study in the United States by Schwartz et al.38

Our study has a number of limitations. The survey included only members of the IBD section which may have excluded other clinicians who care for young patients with IBD. In addition, while our survey did not include primary care physicians, in the UK vast majority of young IBD patients remain under secondary or tertiary care and hence it is unlikely there would have been additional information by including primary care clinicians in this survey. As in other postal surveys there is also potential for response bias as response rate for adult gastroenterologists was just below 50%. There is also potential for bias in relation to social desirability but this could not be adjusted with this survey. In addition, as we used Likert scale with mean rating scores there may be potential for central tendency bias for some of the responses but Likert scale is a validated instrument and has been used in other similar surveys including that of Hait et al.14 and we chose this to aid comparisons from that survey from North America. Finally, while the results of our survey provide some basic understanding of the transition needs and barriers as perceived by the clinicians in United Kingdom involved in the care of IBD patients, differences in health care systems in different countries were not considered within our survey. Clearly, transition care services will need to tailored to the local needs and systems including reimbursing arrangements.

5 Conclusions

This survey suggests that there are differences in the perception of adult and paediatric gastroenterologists in the transition requirements in adolescents with IBD. Bridging the gap in perceptions and a co-ordinated multidisciplinary approach between health care professionals involved in care of adolescents may help to remove the barriers for developing successful transition services. In addition, addressing the training deficiencies identified in this survey will be vital. In the absence of randomised clinical trial data on different models of transition, the perspectives of clinicians involved in young IBD patients' care and the areas of concern elucidated in our survey can direct future endeavours to develop locally relevant transition services. The suggested models of transition needs to be evaluated in randomised controlled trials with clear patient outcome measures such as quality of life, employment and cost effectiveness.

6 Statement of authorship

SS—Conceived the study, designed questionnaires, coordinated the study, analysis and writing of manuscript.

JOL—Conceived the study, involved in design of questionnaires, analysis and writing the manuscript.

HJ, SM, IA, TA, RR, NC—design of questionnaires

All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

This work was presented as an abstract at the ECCO Congress Dublin 2011.

Appendix 1

Questionnaire to adult gastroenterologists

Appendix 2

Questionnaire to paediatric gastroenterologists

References

Figures

Percentage responses of perceived importance of structured transition care.

Ranking of criteria for transfer . x-axis—each bar represents a ranking from 1 to 6, 1 being the highest ranking and 6 being lowest, y-axis—% of responses for each ranking.

Regional representation of respondents.

| Responding adult gastroenterologists | Responding paediatric gastroenterologists | |

| 358 | 82 | |

| Regions | ||

| South of England | 134 (37%) | 39 (47%) |

| Midlands | 63 (17%) | 11 (13%) |

| North and North East | 106 (29%) | 23 (28%) |

| Scotland | 36 (10%) | 4 (5%) |

| Wales | 11 (3%) | 4 (5%) |

| Northern Ireland | 9 (2%) | 1 (1.2%) |

| Hospital Setting | ||

| Teaching Hospital | 141 (39%) | 49 (59%) |

| District General Hospital | 218 (61%) | 33 (41%) |

| Responding adult gastroenterologists | Responding paediatric gastroenterologists | |

| 358 | 82 | |

| Regions | ||

| South of England | 134 (37%) | 39 (47%) |

| Midlands | 63 (17%) | 11 (13%) |

| North and North East | 106 (29%) | 23 (28%) |

| Scotland | 36 (10%) | 4 (5%) |

| Wales | 11 (3%) | 4 (5%) |

| Northern Ireland | 9 (2%) | 1 (1.2%) |

| Hospital Setting | ||

| Teaching Hospital | 141 (39%) | 49 (59%) |

| District General Hospital | 218 (61%) | 33 (41%) |

Regional representation of respondents.

| Responding adult gastroenterologists | Responding paediatric gastroenterologists | |

| 358 | 82 | |

| Regions | ||

| South of England | 134 (37%) | 39 (47%) |

| Midlands | 63 (17%) | 11 (13%) |

| North and North East | 106 (29%) | 23 (28%) |

| Scotland | 36 (10%) | 4 (5%) |

| Wales | 11 (3%) | 4 (5%) |

| Northern Ireland | 9 (2%) | 1 (1.2%) |

| Hospital Setting | ||

| Teaching Hospital | 141 (39%) | 49 (59%) |

| District General Hospital | 218 (61%) | 33 (41%) |

| Responding adult gastroenterologists | Responding paediatric gastroenterologists | |

| 358 | 82 | |

| Regions | ||

| South of England | 134 (37%) | 39 (47%) |

| Midlands | 63 (17%) | 11 (13%) |

| North and North East | 106 (29%) | 23 (28%) |

| Scotland | 36 (10%) | 4 (5%) |

| Wales | 11 (3%) | 4 (5%) |

| Northern Ireland | 9 (2%) | 1 (1.2%) |

| Hospital Setting | ||

| Teaching Hospital | 141 (39%) | 49 (59%) |

| District General Hospital | 218 (61%) | 33 (41%) |

Mean scores of perceived importance of competencies at transfer.

| Competency | Adult gastroenterologists mean score ± SD | Paediatric gastroenterologists mean score ± SD | p-Value |

| Understanding of disease | 4.19 ± 0.87 | 4.33 ± 0.68 | NS |

| Understanding of treatment | 4.22 ± 0.86 | 4.47 ± 0.64 | NS |

| Ability to take medicines independently | 3.97 ± 0.93 | 4.23 ± 0.85 | NS |

| Understanding of impact of smoking on the disease | 3.76 ± 1.03 | 3.57 ± 0.78 | NS |

| Ability to attend clinics without parents | 3.20 ± 1.03 | 3.96 ± 1.16 | 0.02 |

| Ability to undergo endoscopies without anaesthetic | 3.95 ± 1.13 | 3.04 ± 1.22 | 0.01 |

| understanding of impact of diet on the disease | 3.02 ± 0.93 | 3.09 ± 0.97 | NS |

| Membership of patient group | 2.34 ± 1.05 | 2.09 ± 0.99 | NS |

| Competency | Adult gastroenterologists mean score ± SD | Paediatric gastroenterologists mean score ± SD | p-Value |

| Understanding of disease | 4.19 ± 0.87 | 4.33 ± 0.68 | NS |

| Understanding of treatment | 4.22 ± 0.86 | 4.47 ± 0.64 | NS |

| Ability to take medicines independently | 3.97 ± 0.93 | 4.23 ± 0.85 | NS |

| Understanding of impact of smoking on the disease | 3.76 ± 1.03 | 3.57 ± 0.78 | NS |

| Ability to attend clinics without parents | 3.20 ± 1.03 | 3.96 ± 1.16 | 0.02 |

| Ability to undergo endoscopies without anaesthetic | 3.95 ± 1.13 | 3.04 ± 1.22 | 0.01 |

| understanding of impact of diet on the disease | 3.02 ± 0.93 | 3.09 ± 0.97 | NS |

| Membership of patient group | 2.34 ± 1.05 | 2.09 ± 0.99 | NS |

Scores: 1 = Not important, 2 = minimal importance, 3 = of moderate importance, 4 = very important but not essential, 5 = very important and essential.

Mean scores of perceived importance of competencies at transfer.

| Competency | Adult gastroenterologists mean score ± SD | Paediatric gastroenterologists mean score ± SD | p-Value |

| Understanding of disease | 4.19 ± 0.87 | 4.33 ± 0.68 | NS |

| Understanding of treatment | 4.22 ± 0.86 | 4.47 ± 0.64 | NS |

| Ability to take medicines independently | 3.97 ± 0.93 | 4.23 ± 0.85 | NS |

| Understanding of impact of smoking on the disease | 3.76 ± 1.03 | 3.57 ± 0.78 | NS |

| Ability to attend clinics without parents | 3.20 ± 1.03 | 3.96 ± 1.16 | 0.02 |

| Ability to undergo endoscopies without anaesthetic | 3.95 ± 1.13 | 3.04 ± 1.22 | 0.01 |

| understanding of impact of diet on the disease | 3.02 ± 0.93 | 3.09 ± 0.97 | NS |

| Membership of patient group | 2.34 ± 1.05 | 2.09 ± 0.99 | NS |

| Competency | Adult gastroenterologists mean score ± SD | Paediatric gastroenterologists mean score ± SD | p-Value |

| Understanding of disease | 4.19 ± 0.87 | 4.33 ± 0.68 | NS |

| Understanding of treatment | 4.22 ± 0.86 | 4.47 ± 0.64 | NS |

| Ability to take medicines independently | 3.97 ± 0.93 | 4.23 ± 0.85 | NS |

| Understanding of impact of smoking on the disease | 3.76 ± 1.03 | 3.57 ± 0.78 | NS |

| Ability to attend clinics without parents | 3.20 ± 1.03 | 3.96 ± 1.16 | 0.02 |

| Ability to undergo endoscopies without anaesthetic | 3.95 ± 1.13 | 3.04 ± 1.22 | 0.01 |

| understanding of impact of diet on the disease | 3.02 ± 0.93 | 3.09 ± 0.97 | NS |

| Membership of patient group | 2.34 ± 1.05 | 2.09 ± 0.99 | NS |

Scores: 1 = Not important, 2 = minimal importance, 3 = of moderate importance, 4 = very important but not essential, 5 = very important and essential.

Mean scores of perceived patient/parent and organisational barriers to successful transition.

| Potential barriers | Adult gastroenterologists mean score ± SD | Paediatric gastroenterologists mean score ± SD | p-Value |

| Patients' limited understanding of condition and treatment | 4.12 ± 0.81 | 3.09 ± 0.67 | 0.04 |

| Lack of self advocacy | 3.89 ± 0.87 | 4.04 ± 0.84 | NS |

| Parental reluctance to transition | 3.57 ± 1.03 | 3.63 ± 0.84 | NS |

| Patients/parent's high expectation | 3.59 ± 0.97 | 3.68 ± 0.83 | NS |

| Lack of space/Time | 3.93 ± 1.03 | 4.22 ± 0.71 | NS |

| Lack of supportive services (nurses,admin etc.) | 3.92 ± 1.06 | 4.09 ± 0.97 | NS |

| Lack of funding | 3.59 ± 1.22 | 3.77 ± 1.19 | NS |

| Clinicians lack of trust in relevant clinical services | 3.12 ± 0.64 | 4.19 ± 0. 51 | 0.01 |

| Lack of interest in relevant colleagues | 3.08 ± 1.24 | 3.90 ± 1.15 | 0.02 |

| Lack of defined policies | 3.32 ± 1.07 | 3.40 ± 1.09 | NS |

| Potential barriers | Adult gastroenterologists mean score ± SD | Paediatric gastroenterologists mean score ± SD | p-Value |

| Patients' limited understanding of condition and treatment | 4.12 ± 0.81 | 3.09 ± 0.67 | 0.04 |

| Lack of self advocacy | 3.89 ± 0.87 | 4.04 ± 0.84 | NS |

| Parental reluctance to transition | 3.57 ± 1.03 | 3.63 ± 0.84 | NS |

| Patients/parent's high expectation | 3.59 ± 0.97 | 3.68 ± 0.83 | NS |

| Lack of space/Time | 3.93 ± 1.03 | 4.22 ± 0.71 | NS |

| Lack of supportive services (nurses,admin etc.) | 3.92 ± 1.06 | 4.09 ± 0.97 | NS |

| Lack of funding | 3.59 ± 1.22 | 3.77 ± 1.19 | NS |

| Clinicians lack of trust in relevant clinical services | 3.12 ± 0.64 | 4.19 ± 0. 51 | 0.01 |

| Lack of interest in relevant colleagues | 3.08 ± 1.24 | 3.90 ± 1.15 | 0.02 |

| Lack of defined policies | 3.32 ± 1.07 | 3.40 ± 1.09 | NS |

Scores: 1 = Not important, 2 = don't know 3 = minimally important, 4 = moderately important, 5 = very important.

Mean scores of perceived patient/parent and organisational barriers to successful transition.

| Potential barriers | Adult gastroenterologists mean score ± SD | Paediatric gastroenterologists mean score ± SD | p-Value |

| Patients' limited understanding of condition and treatment | 4.12 ± 0.81 | 3.09 ± 0.67 | 0.04 |

| Lack of self advocacy | 3.89 ± 0.87 | 4.04 ± 0.84 | NS |

| Parental reluctance to transition | 3.57 ± 1.03 | 3.63 ± 0.84 | NS |

| Patients/parent's high expectation | 3.59 ± 0.97 | 3.68 ± 0.83 | NS |

| Lack of space/Time | 3.93 ± 1.03 | 4.22 ± 0.71 | NS |

| Lack of supportive services (nurses,admin etc.) | 3.92 ± 1.06 | 4.09 ± 0.97 | NS |

| Lack of funding | 3.59 ± 1.22 | 3.77 ± 1.19 | NS |

| Clinicians lack of trust in relevant clinical services | 3.12 ± 0.64 | 4.19 ± 0. 51 | 0.01 |

| Lack of interest in relevant colleagues | 3.08 ± 1.24 | 3.90 ± 1.15 | 0.02 |

| Lack of defined policies | 3.32 ± 1.07 | 3.40 ± 1.09 | NS |

| Potential barriers | Adult gastroenterologists mean score ± SD | Paediatric gastroenterologists mean score ± SD | p-Value |

| Patients' limited understanding of condition and treatment | 4.12 ± 0.81 | 3.09 ± 0.67 | 0.04 |

| Lack of self advocacy | 3.89 ± 0.87 | 4.04 ± 0.84 | NS |

| Parental reluctance to transition | 3.57 ± 1.03 | 3.63 ± 0.84 | NS |

| Patients/parent's high expectation | 3.59 ± 0.97 | 3.68 ± 0.83 | NS |

| Lack of space/Time | 3.93 ± 1.03 | 4.22 ± 0.71 | NS |

| Lack of supportive services (nurses,admin etc.) | 3.92 ± 1.06 | 4.09 ± 0.97 | NS |

| Lack of funding | 3.59 ± 1.22 | 3.77 ± 1.19 | NS |

| Clinicians lack of trust in relevant clinical services | 3.12 ± 0.64 | 4.19 ± 0. 51 | 0.01 |

| Lack of interest in relevant colleagues | 3.08 ± 1.24 | 3.90 ± 1.15 | 0.02 |

| Lack of defined policies | 3.32 ± 1.07 | 3.40 ± 1.09 | NS |

Scores: 1 = Not important, 2 = don't know 3 = minimally important, 4 = moderately important, 5 = very important.